On June 16th, 2012, eight years ago today, I married the woman I love. I was fortune to have found her and to have shared the past decade of my life with her. Our lives have changes significantly since we met - it seems like lifetimes ago that we exchanged our vows under an unexpected swarm of dragonflies (which we have since adopted as a symbol of our union), and in some ways it has been a lifetime. We don't live in the same small apartment or even the same state we started in and we've both changed jobs and industries multiple times. We've shared fantastic travel experiences and weathered challenges including recessions, snowstorms, hurricanes, protests and more recently a global pandemic. And through it all I could not hope to have found a more adaptable, genuine and supportive partner. I am constantly reminded that it takes a very special and patient kind of person to deal with me for ten minutes let alone a full decade, but she nods and smiles and shares the ride with me, even when my trajectory and train of thought go off the rails and crash through terrain that neither of us are familiar with. For that I am eternally grateful.

The piece below was previously published in my ebook of poetry, "Turning the Stars." It's every bit as relevant now as it was when I first wrote it. Having a true partner, I have learned, means having someone who accepts all of your quirks and oddities and history, even if it doesn't always make sense.

Young Summer Gibberish

We were kids

without fences,

without unlimited

text messaging -

who needed that, when

a magic eight ball

could tell us

all we needed to know -

to call someone or not.

Text-based computer games -

pale green glowing cursor

(a green you never see

anymore, except on

monitors in old movies),

awaiting our commands

while the high definition

wilderness behind

our friends' houses

stretched across the planet.

We learned

kabbalistic quack

Cracker Jack magic tricks

to cure migraines

in dust mote choked

sunbeams through the rafters

of a day camp barn loft –

one hand on the forehead

and one hand behind the head

palms facing each other

"visualize streams

of deep blue and green and

aqua."

Maybe when I tell you

all these things, like a deluge of

verbal pop cap candy fizz trivia, you'll

tilt your head to a cascade of dark hair;

your burnt umber eyes

hanging slightly ajar.

Baffled, both of us

for a moment until

you put your hand in mine,

letting me know

you don't mind

my gibberish.

Tuesday, June 16, 2020

Friday, June 12, 2020

Ryman Alley

When I travel, I'm usually focused on going from one place to the next to the next, but sometimes the places between places have their own stories to tell. (The piece below was previously published on Atlas Obscura. You can see it here.)

The alley connecting two of country music's most historic venues has a rich history of its own.

Walking from the gates of the Ryman Auditorium (which hosted the Grande Ole Opry for a time) to the back door of Tootsies Orchard Lounge is, for country music fans, akin to a short but holy pilgrimage.

It’s hard to fathom just how many country music superstars have passed between the Ryman Auditorium and Tootsies over the years. Willie Nelson, Patsy Cline, Chet Atkins, and Hank Williams are just a few of the famous musicians to walk this alley. Nelson, in fact, immortalized the alley in a song line “seventeen steps to Tootsies and thirty-four back,” presumably alluding to having a few cocktails at the lounge and staggering out afterward.

According to legends, the alley between the venues actually became a venue itself. During the 1950s, two young boys would sing and play guitar to Opry stars passing by in hopes of catching their attention. Night after night they played the alley, honing their craft and hoping for a break.

That break came when Chet Atkins happened to pass by and offered the boys a chance to perform with him on stage at the Opry that night. They were only too happy to do so, and went on to achieve stardom of their own as the Everly Brothers.

If you pass through the alley, you can follow, literally, in the footsteps of country music legends. A set of footprints have been inlaid on the ground.

Wednesday, June 10, 2020

Deeper South

I've lived in Tampa now for almost four years, and I've found acceptance here. It took plenty of salt water to wash all the layers of big northern cities from my skin, but I feel like I fit in now. Some of that has to do as much with the place as with me - Florida has been host to transplants for centuries - the Spanish, the English, Americans and more recently "northerners." In my travels though, I've found that some southern cities and towns are less accepting of this, and though they invite you in with a warm smile and a beer-battered meal, they subtly and politely remind you that their south and yours are not the same thing.

You can gawk and point fingers

At the monuments to those

Of cursed memory.

Snap pictures on the sly

Of the bones of the saints

And the Fiji Mermaids

That we keep shackled

In the vaults of our cathedrals.

Fumble your blunt tongue

Over the broken sidewalks

Of our quaint street names and sayings.

But it isn’t your blood

That once cut rivers through the

Fields coarse hands work.

Those names carved in the stones

Set atop that hill, they

Aren’t any relations of yours.

Deeper South

You can gawk and point fingers

At the monuments to those

Of cursed memory.

Snap pictures on the sly

Of the bones of the saints

And the Fiji Mermaids

That we keep shackled

In the vaults of our cathedrals.

Fumble your blunt tongue

Over the broken sidewalks

Of our quaint street names and sayings.

But it isn’t your blood

That once cut rivers through the

Fields coarse hands work.

Those names carved in the stones

Set atop that hill, they

Aren’t any relations of yours.

To you it’s a second language;

Rebranding our memories

With your Instagram photos.

Rebranding our memories

With your Instagram photos.

You’re fashioned from data analytics,

Not shale or corn cob, or red clay

Bound in plastic, not kudzu, and

The deep delta mud under your fingernails

Wasn’t born there.

As a child, you never learned the rhymes

That teach you which path will grant you

Safe passage past the witch’s cave.

Not shale or corn cob, or red clay

Bound in plastic, not kudzu, and

The deep delta mud under your fingernails

Wasn’t born there.

As a child, you never learned the rhymes

That teach you which path will grant you

Safe passage past the witch’s cave.

So occupy the outer rings of our circles

Sample our music and shine

Purchase a plot of land,

But know you well,

Not one or all

Of those things

Will ever make you

From here.

Sample our music and shine

Purchase a plot of land,

But know you well,

Not one or all

Of those things

Will ever make you

From here.

Friday, June 5, 2020

Exploring Central Florida: Hidden Black History

In my travels throughout Florida and the southeastern US as a whole, visiting various lesser known monuments and historical sites has revealed to me a stark and disheartening difference in the way some of them have been preserved. While removing or relocating confederate civil war monuments and statues has triggered outrage among some (especially and not surprisingly white supremacy groups), important historical reminders of black history such as cemeteries and, in at least one case, an entire town that was destroyed by racial violence, have been plowed over and erased from the map for decades with hardly any notice. In the wake of George Floyd's murder and the ongoing protests around the country over systemic racism and police brutality, it seemed like the right time to shine a spotlight on some of these little known spots. There are a great many other sites, including those along the Florida Black Heritage Trail, but this just reflects some of those with which I am most familiar.

1. The Harlem of the South

During segregation, roughly half of all black people living in Tampa occupied the area known as the Scrub. Central Avenue there became the black business and entertainment district, known as the Harlem of the South, with almost 100 shops and storefronts. Those businesses included a boarding house where "The St. Pete Blues" was recorded by a little known musician at the time named Ray Charles. That song would go on to be his first major hit. Today Central Ave is the site of Perry Harvey, Sr. Park and displays along the sidewalk illustrate the development, culture, history and key figures that made Central Avenue a success up until it's decline the sixties. The shooting of a 19-year-old black man named Martin Chambers by a white police officer in 1967 led to rioting and essentially closed the chapter on Central Avenue's many decades of prosperity.

2. Progress, One Step at a Time

In other posts I've mentioned my deep affection for St. Augustine, with it's centuries of history dating back to Spanish and English occupation. On a more recent trip there, I discovered that it also contains an important piece of much more recent, Civil Rights history, in the form of several bronze footprints near the corner of King Street and St. George Street. Known as Andrew Young's Crossing, the footprints terminate abruptly at the spot where the young activist was knocked unconscious by an angry white mob while leading a peaceful protest march on behalf of Dr. Martin Luther King. Young and his marchers remained true to the ideal of passive resistance and endured the brutal beatings. This has been cited as one of the events which led President Lyndon Johnson to pass the Civil Rights Bill on July 2nd, 1964. Young went on to become America's first African American U.N. Ambassador and subsequently Mayor of Atlanta. He has since returned to St. Augustine multiple times, completing the path from which he was once forcefully prevented.

3. Where is Rosewood?

If you've ever visited the quaint beach community of Cedar Key, you likely drove past a historical marker along Florida State Road 24. That marker is essentially all that remains of the town of Rosewood, which was torn apart and set ablaze when racial tensions erupted into a violent massacre. Rosewood was once a peaceful lumber town, but that all changed on January 1st, 1923 when a white woman accused a black man there of assaulting her. According to the marker, "In the search for her alleged attacker, whites terrorized and killed Rosewood residents. In the days of fear and violence that followed, many Rosewood citizens sought refuge in the nearby woods. White merchant John M. Wright and other courageous whites sheltered some of the fleeing men, women and children. Whites burned Rosewood and looted livestock and property; two were killed while attacking a home. Five blacks also lost their lives: Sam Carter, who was tortured for information and shot to death." The death toll is actually now believed to have much higher and that the female accuser was trying to cover up an affair. Though profoundly tragic and disturbing, many have not heard of the events that transpired in Rosewood, because for almost 60 years the massacre was a taboo subject, until former residents began reluctantly opening up about it in 1982.

4. Green Benches, Invisible Bars

As far back as 1916, the city of St. Petersburg knew it was going to become a major tourist destination. Toward this end, Mayor Al Lang realized that amid the beaches, shopping and other attractions, visitors would appreciate a comfortable place to sit. So he began regulating the dimensions, size and color (green) of the benches around the city. Thousands of them sprung up - you can still see the smiling faces of people sitting on them in old postcards. Smiling, old, white faces, that is. According to Ray Arsenault – John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, "the black residents of St. Petersburg had their place, but that place was not on the green benches." They weren't expressly forbidden from them, but they didn't have to be - it was simply understood. Eventually, in the 1960's, the City realized the error they had made and removed the benches in an attempt to rebrand the city as younger as more diverse. But the damage was done and the connections between the green benches and systemic racism was inseparable. Today you can still find one of those few remaining green benches in the Florida Holocaust Museum.

5. Separate and Unequal... in Death as in Life

I dedicated a chapter to this subject in my upcoming book, "Secret Tampa Bay: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful and Obscure," and the story is unfolding in real time as more cemeteries are discovered, so I won't say too much about it. Suffice it to say that as many as a dozen of the Tampa Bay area's oldest black cemeteries very quietly slipped off the map and became lost. The oldest of these, Zion Cemetery, was recently discovered to have been underneath public housing for the last 70 years. In their haste to cash in on available land, the developers never even bothered to move the coffins. To compound the pain of those family members who are learning that the graves of their relatives were ignored and built over, many of the residents there have had to be relocated. More recently another black cemetery was discovered under a local high school and now it appears that a third may have been found in Clearwater. Still others will likely be rediscovered in the coming days - a painful reminder of how black history and bodies have been bulldozed, erased and forgotten.

As mentioned previously - these are just a very few of the vast number of historically and culturally significant black history sites in central Florida. There's the home of Zora Neale Hurston, Fort Mose, the Bing Rooming House Museum, school houses, churches, cemeteries and monuments. I plan to explore this topic further, and I look forward, as always, to sharing with you what I discover.

1. The Harlem of the South

During segregation, roughly half of all black people living in Tampa occupied the area known as the Scrub. Central Avenue there became the black business and entertainment district, known as the Harlem of the South, with almost 100 shops and storefronts. Those businesses included a boarding house where "The St. Pete Blues" was recorded by a little known musician at the time named Ray Charles. That song would go on to be his first major hit. Today Central Ave is the site of Perry Harvey, Sr. Park and displays along the sidewalk illustrate the development, culture, history and key figures that made Central Avenue a success up until it's decline the sixties. The shooting of a 19-year-old black man named Martin Chambers by a white police officer in 1967 led to rioting and essentially closed the chapter on Central Avenue's many decades of prosperity.

2. Progress, One Step at a Time

In other posts I've mentioned my deep affection for St. Augustine, with it's centuries of history dating back to Spanish and English occupation. On a more recent trip there, I discovered that it also contains an important piece of much more recent, Civil Rights history, in the form of several bronze footprints near the corner of King Street and St. George Street. Known as Andrew Young's Crossing, the footprints terminate abruptly at the spot where the young activist was knocked unconscious by an angry white mob while leading a peaceful protest march on behalf of Dr. Martin Luther King. Young and his marchers remained true to the ideal of passive resistance and endured the brutal beatings. This has been cited as one of the events which led President Lyndon Johnson to pass the Civil Rights Bill on July 2nd, 1964. Young went on to become America's first African American U.N. Ambassador and subsequently Mayor of Atlanta. He has since returned to St. Augustine multiple times, completing the path from which he was once forcefully prevented.

3. Where is Rosewood?

If you've ever visited the quaint beach community of Cedar Key, you likely drove past a historical marker along Florida State Road 24. That marker is essentially all that remains of the town of Rosewood, which was torn apart and set ablaze when racial tensions erupted into a violent massacre. Rosewood was once a peaceful lumber town, but that all changed on January 1st, 1923 when a white woman accused a black man there of assaulting her. According to the marker, "In the search for her alleged attacker, whites terrorized and killed Rosewood residents. In the days of fear and violence that followed, many Rosewood citizens sought refuge in the nearby woods. White merchant John M. Wright and other courageous whites sheltered some of the fleeing men, women and children. Whites burned Rosewood and looted livestock and property; two were killed while attacking a home. Five blacks also lost their lives: Sam Carter, who was tortured for information and shot to death." The death toll is actually now believed to have much higher and that the female accuser was trying to cover up an affair. Though profoundly tragic and disturbing, many have not heard of the events that transpired in Rosewood, because for almost 60 years the massacre was a taboo subject, until former residents began reluctantly opening up about it in 1982.

4. Green Benches, Invisible Bars

As far back as 1916, the city of St. Petersburg knew it was going to become a major tourist destination. Toward this end, Mayor Al Lang realized that amid the beaches, shopping and other attractions, visitors would appreciate a comfortable place to sit. So he began regulating the dimensions, size and color (green) of the benches around the city. Thousands of them sprung up - you can still see the smiling faces of people sitting on them in old postcards. Smiling, old, white faces, that is. According to Ray Arsenault – John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, "the black residents of St. Petersburg had their place, but that place was not on the green benches." They weren't expressly forbidden from them, but they didn't have to be - it was simply understood. Eventually, in the 1960's, the City realized the error they had made and removed the benches in an attempt to rebrand the city as younger as more diverse. But the damage was done and the connections between the green benches and systemic racism was inseparable. Today you can still find one of those few remaining green benches in the Florida Holocaust Museum.

5. Separate and Unequal... in Death as in Life

I dedicated a chapter to this subject in my upcoming book, "Secret Tampa Bay: A Guide to the Weird, Wonderful and Obscure," and the story is unfolding in real time as more cemeteries are discovered, so I won't say too much about it. Suffice it to say that as many as a dozen of the Tampa Bay area's oldest black cemeteries very quietly slipped off the map and became lost. The oldest of these, Zion Cemetery, was recently discovered to have been underneath public housing for the last 70 years. In their haste to cash in on available land, the developers never even bothered to move the coffins. To compound the pain of those family members who are learning that the graves of their relatives were ignored and built over, many of the residents there have had to be relocated. More recently another black cemetery was discovered under a local high school and now it appears that a third may have been found in Clearwater. Still others will likely be rediscovered in the coming days - a painful reminder of how black history and bodies have been bulldozed, erased and forgotten.

As mentioned previously - these are just a very few of the vast number of historically and culturally significant black history sites in central Florida. There's the home of Zora Neale Hurston, Fort Mose, the Bing Rooming House Museum, school houses, churches, cemeteries and monuments. I plan to explore this topic further, and I look forward, as always, to sharing with you what I discover.

Tuesday, May 19, 2020

Wonderloss

"Left," Jason says from the back seat.

I flip the turn signal and make the next left. The beams of the headlights of my Ford Taurus slice through the jet black darkness as the road bends and curves under a canopy of trees.

After we pass a half dozen intersections, Steve jumps in with a "right."

I flip on the turn signal again and we wind deeper into the unknown, my friends alternating in giving instructions.

We didn't do it that often and the three of us didn't spend a lot of time together. I was the shared friend between the two of them - Jason, with whom I went to the same high school and Steve with whom I had grown up. I seem to recall that the three of us had just finished a new issue of Dharmacation, which was the successor to Driftwood, the magazine that Steve and Geoff and I had had started together - a local zine/literary magazine (possibly one of the very first to include online submissions). Geoff had moved on to other projects and Steve and I had continued our endeavors under a new name, and brought Jason in. It didn't have the same dynamic, but it worked well enough, for a while.

Our goal that particular evening was just to get as far from what we knew as we could, while still being "responsible" enough to get back home at a reasonable time. I was living with my dad at that point and he may or may not have been traveling in some other state or country, so "a reasonable time" was pretty loosely defined. Generally I interpreted it to mean at least a couple hours before sunrise.

The few times we tried this activity/experiment or whatever you want to call it, we seemed to always end up in Morrisville out around New Hope and the New Jersey border. The challenge was to get to some place we had never been before, and then see if we could retrace our route back to those roads and streets that we knew like the back of our hands.

It was a weird bonding activity, but hey, we were weird kids. While some kids drank or smoked or played with drugs, our form of rebellion manifested itself in trying to get lost - something that each of us had been advised to do on a fairly frequent basis. And as we attempted to get lost and then unlost, we listened to punk rock and alternative music, or we just turned the radio on and listed to the Princeton college radio station. I think REM's album, Automatic for the People came out around that time - maybe that's what we were listening to.

There was a sense of satisfaction when we finally realized that we had achieved our goal and nothing looked familiar anymore. And there was an equal sense of accomplishment in getting back to our small known world. Manufactured stress and artificial relief - but to us it was real enough.

And now, nearly 30 years later, Steve is gone, Jason is somewhere, and I find that I'm doing something similar to what the three of us did together as teenagers. I go for long drives, hours some times, looking for something I haven't seen before. It's different now in that I always know where I'm going - I have a specific destination in mind. And you can't really get lost anymore - not with seemingly every point on earth now mapped out in a smartphone application. I don't have to stop and ask for directions, unless what I'm looking for is really hard to find - a miniature roadside monument, an abandoned cabin deep in a swamp, an enigmatic gravestone or something to that effect. It's never because I don't know where I am.

Having to pull into a gas station and have someone behind the counter pull out a map and puzzle over how the hell we ended up wherever the hell we did - that's probably not an experience that teenagers today or at any time in the future will be able to relate to. We've lost our ability to be lost, and with it, I think, something important, a kind of wonder. Or rather, the potential for wonder. We don't puzzle over what's around the next bend in the street - we can see it all on google maps. Where to stop for a snack, where to fill up with gas, where to take the best picture - it's all right there at our fingertips. But once known, once the route is planned and plotted and mapped, it cannot ever again be unknown. There are some things that can only be found when you're not looking for anything. And for all the big, ten dollar words I've so carefully accumulated and collected over the years, I have trouble articulating quite how that makes me feel - trying to hold onto a shared memory when those you shared it with and when even the very world in which you shared it have all vanished. Wonderloss, I guess; a very specific type of nostalgia heartache, and it's heavy on me tonight as I write this.

I feel rather than hear that familiar, silent voice whispering, "go on, get out of here. Get lost...

...if you remember how."

I flip the turn signal and make the next left. The beams of the headlights of my Ford Taurus slice through the jet black darkness as the road bends and curves under a canopy of trees.

After we pass a half dozen intersections, Steve jumps in with a "right."

I flip on the turn signal again and we wind deeper into the unknown, my friends alternating in giving instructions.

We didn't do it that often and the three of us didn't spend a lot of time together. I was the shared friend between the two of them - Jason, with whom I went to the same high school and Steve with whom I had grown up. I seem to recall that the three of us had just finished a new issue of Dharmacation, which was the successor to Driftwood, the magazine that Steve and Geoff and I had had started together - a local zine/literary magazine (possibly one of the very first to include online submissions). Geoff had moved on to other projects and Steve and I had continued our endeavors under a new name, and brought Jason in. It didn't have the same dynamic, but it worked well enough, for a while.

Our goal that particular evening was just to get as far from what we knew as we could, while still being "responsible" enough to get back home at a reasonable time. I was living with my dad at that point and he may or may not have been traveling in some other state or country, so "a reasonable time" was pretty loosely defined. Generally I interpreted it to mean at least a couple hours before sunrise.

The few times we tried this activity/experiment or whatever you want to call it, we seemed to always end up in Morrisville out around New Hope and the New Jersey border. The challenge was to get to some place we had never been before, and then see if we could retrace our route back to those roads and streets that we knew like the back of our hands.

It was a weird bonding activity, but hey, we were weird kids. While some kids drank or smoked or played with drugs, our form of rebellion manifested itself in trying to get lost - something that each of us had been advised to do on a fairly frequent basis. And as we attempted to get lost and then unlost, we listened to punk rock and alternative music, or we just turned the radio on and listed to the Princeton college radio station. I think REM's album, Automatic for the People came out around that time - maybe that's what we were listening to.

There was a sense of satisfaction when we finally realized that we had achieved our goal and nothing looked familiar anymore. And there was an equal sense of accomplishment in getting back to our small known world. Manufactured stress and artificial relief - but to us it was real enough.

And now, nearly 30 years later, Steve is gone, Jason is somewhere, and I find that I'm doing something similar to what the three of us did together as teenagers. I go for long drives, hours some times, looking for something I haven't seen before. It's different now in that I always know where I'm going - I have a specific destination in mind. And you can't really get lost anymore - not with seemingly every point on earth now mapped out in a smartphone application. I don't have to stop and ask for directions, unless what I'm looking for is really hard to find - a miniature roadside monument, an abandoned cabin deep in a swamp, an enigmatic gravestone or something to that effect. It's never because I don't know where I am.

Having to pull into a gas station and have someone behind the counter pull out a map and puzzle over how the hell we ended up wherever the hell we did - that's probably not an experience that teenagers today or at any time in the future will be able to relate to. We've lost our ability to be lost, and with it, I think, something important, a kind of wonder. Or rather, the potential for wonder. We don't puzzle over what's around the next bend in the street - we can see it all on google maps. Where to stop for a snack, where to fill up with gas, where to take the best picture - it's all right there at our fingertips. But once known, once the route is planned and plotted and mapped, it cannot ever again be unknown. There are some things that can only be found when you're not looking for anything. And for all the big, ten dollar words I've so carefully accumulated and collected over the years, I have trouble articulating quite how that makes me feel - trying to hold onto a shared memory when those you shared it with and when even the very world in which you shared it have all vanished. Wonderloss, I guess; a very specific type of nostalgia heartache, and it's heavy on me tonight as I write this.

I feel rather than hear that familiar, silent voice whispering, "go on, get out of here. Get lost...

...if you remember how."

Wednesday, May 13, 2020

Treasury Street

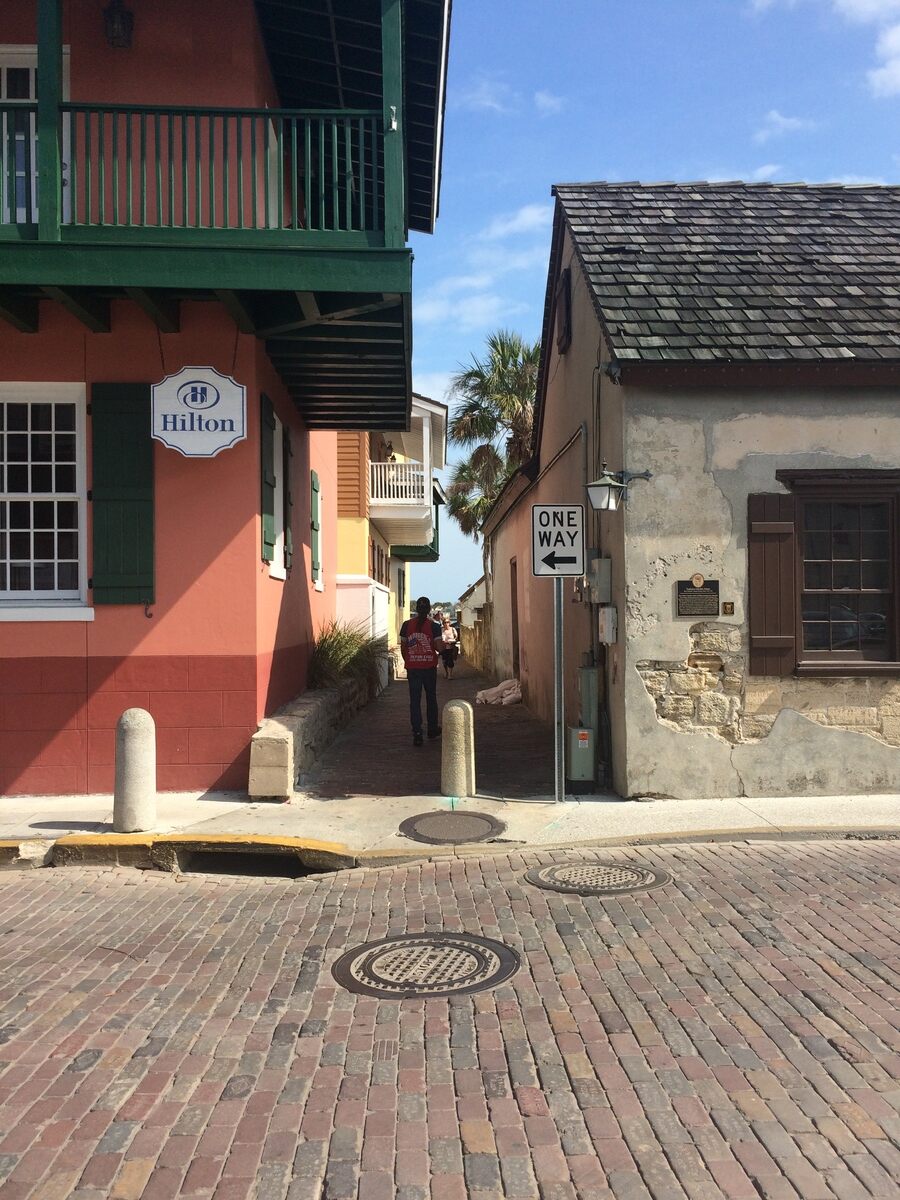

Since I recently shared my St. Augustine Adventure List, I thought I would delve a bit deeper into one of the locations mentioned in that post (The piece below was previously published on Atlas Obscura. You can see it here).

St. Augustine's record-setting narrow street was designed to protect against pirates.

Measuring just seven feet wide, St. Augustine's Treasury Street may be the narrowest street in the United States. And the lane is skinny by design.

Treasury Street connects Bay Street on the waterfront with what used to be the Royal Spanish Treasury. Local legend says the street was built just wide enough for two men to carry a chest of gold to and from ships docked on the bay, but not wide enough for a horse-drawn carriage to squeeze through and ride off with the money. In the former Spanish port, piracy was a serious concern, especially in the walk between the bank and the bay.

Monday, May 11, 2020

Secret Tampa Bay Bonus Content: Insectile Orgy of Death

When I started writing Secret Tampa Bay, I wasn't sure how I could possibly fill 206 pages. After several months of work though, I ended up not with too little content, but rather with far more than I could possibly include. Deciding what to omit was difficult as I'm proud of the research and writing I did on each chapter - consequently I'll be sharing here some of that extra content here with you.

Know your amorous insects: Lovebugs are annoying but harmless. Kissing bugs, on the other hand, are nocturnal, bloodsucking parasites that carry an inflammatory infectious disease which can be deadly.

This particular piece I decided not to include for two reasons: 1) with so many things that readers might want to explore in the Tampa Bay Area, I didn't think it was the right choice to include something that they would probably rather not experience, and 2) the phenomenon known as "lovebug season" isn't really specific to Tampa Bay - the nasty little things can be found in multiple states throughout the southeast and along the Gulf coast. They are presently out in force, so it seemed like the ideal time to share this with you.

Insectile Orgy

of Death

What are all

those nasty-looking little things stuck to everyone’s front fenders and

windshields?

The subject of this chapter highlights not something you’ll likely want

to rush out to experience for yourself, but rather something you might prefer

to avoid, if you can. And it revolves around the two words that makes

motorists, visitors and even long-time residents consider an indoors activity:

lovebug season.

The first documented reference to lovebugs (Plecia Nearctica) along the

Gulf Coast can be traced to Louisiana in the early 1900’s. At the time their

known habitat included Florida, Texas, Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi.

Since then they have spread to Georgia, South Carolina and elsewhere.

Most years see two lovebug seasons, each lasting a few weeks. Typically

the first season occurs sometime in April and the second around late August.

During these periods, millions of these sex-crazed insects will mate and

remain conjoined, even after one of the pair has died, and take to the sky.

Clouds of lovebugs will then hover lazily over any light colored or

light-reflective surface (including highways and cars).

They don’t pose any threat to humans as far as bites or stings –

although they do cause plenty of individuals to swat at the air and themselves

as if suffering from a fit of the world’s worst dance moves. They are also a

nuisance to drivers against whose windshields they tend to splatter, and due to

the acidity of their body chemist, if not removed fairly quickly from

automobiles, their remains become exceedingly difficult to wipe away.

Despite evidence of natural migration, there remains a persistent myth

that lovebugs were genetically modified and introduced to the area (either

accidentally or intentionally) by the University of Florida or some other

research organization in a failed attempt to curb mosquito populations.

Know your amorous insects: Lovebugs are annoying but harmless. Kissing bugs, on the other hand, are nocturnal, bloodsucking parasites that carry an inflammatory infectious disease which can be deadly.

Public

Display of Annihilation

What: Lovebugs

Where: Everywhere you least want them to be.

Cost: None, unless you factor in the cost of a good carwash

Pro Tip: Bug repellant won’t keep away lovebugs, but it will help with

mosquitos and biting flies. Always keep some handy.

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)